A bit of background

Researching violence on social media, I look at language, memes, GIFs, emojis, the weight of violence in a retweet, and a whole range of other instances of violence as they occur on the internet. This is a topic I have been interested in for years and now it is the focus of my PhD. It’s a sprawling topic, much like the World Wide Web itself.

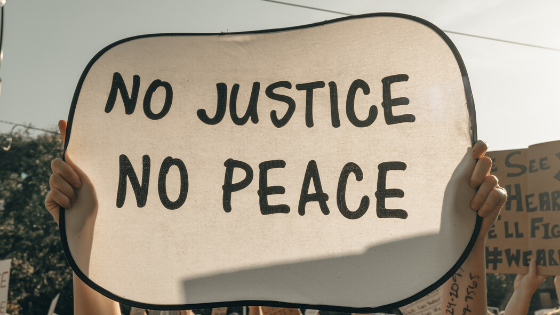

In light of the Black Lives Matter revolution gaining more traction and attention than ever before, antiracism is an understandably amplified topic both online and off. Of course, much of the current conversation is performative – that’s what happens when you haven’t done the work up til now. It’s not like people haven’t been talking about racism around the world for hundreds of years. People have just chosen to listen, to actively silence and place their own comfort above the safety of those affected by white supremacy. However, with more people joining these conversations, there are some patterns emerging that are a continuation of racism in digital spaces.

Back it up a bit

We’re living in the age of the internet. Many of the conversations we have about racism, antiracism and white supremacy are happening online. In theory, this is a great thing. Accessibility is hugely important, as are inclusion and diversity. The digital age should allow us to give space to educators, activists, those with lived experience and let us learn from a range of people across the world. However, the way we use much of the internet – especially social media – doesn’t often allow for this in practice. One of the reasons for this is the fact that poverty overwhelmingly affects Black, Indigenous and People of Colour. Access is not a simple issue and intersecting barriers like racism, poverty and problems faced by those with other marginalised identities compound the inaccessible nature of social media for many of the important conversations where these people’s voices are most needed.

Another problem is that Black, Indigenous and People of Colour are routinely silenced on social media platforms. The algorithms are biased and do not amplify marginalised users where they should. Platform safety policies rarely do enough to protect users, but often are used against marginalised users to silence them when they speak out about the racism they’re experiencing on the platforms and in wider society. Then there’s the racist platform users who leave comments, share content and post their own content with the intent to harm; creating hostile environments for Black, Indigenous and People of Colour on the platforms. Coordinated attacks routinely see the deplatforming of Black, Indigenous and Poeple of Colour whose powerful voices condemn racism, white supremacy and a number of related social issues (e.g. whorephobia, homophobia, biphobia, transphobia, poverty, class systems, misogyny).

Effective communication online

Another problem is that nuance can be difficult to communicate online. When you rely on images and text (especially with character limits), you often lose tone, facial expression, and context for starters. Videos often have a time limit. Posts can be taken out of context. Intention is hard to discern online and perception can be nearly impossible to predict (this is all stuff I’m picking apart in my thesis and to date I have no real answer for rectifying this issue). We have come to view certain actions as agreement, even when there’s no accompanying text to contextualise sharing or liking a post. We are seeing that platform users are finding ways around implicit messaging attached to actions like shares and likes. On Twitter, for example, we see people screenshotting tweets and images for resharing to minimise amplification of content (which at times is done to minimise harm, other times to capture ‘receipts’ or proof that the content did exist, should it be deleted). However, the fact remains that fully understanding someone’s point of view can be very difficult with the limited context and content provided by social media – particularly where there’s a lack of audiovisual components.

Internet communication is endlessly complex. Tackling complex issues on platforms where intention can be misunderstood does not bode well for positive exchange, civil discussion or learning. Every user has a unique relationship with the technology they use and a unique approach to their engagement with the platforms they use. Those relationships will depend on a number of things, not least their prior experience with the internet, their understanding of their own identity, their understanding of how identity construction online, their relationships with the people they interact with on the platform and their understanding of how others view them on that platform. Like I said, it’s complex stuff. Much of this work is subconscious, largely because our education on internet existence, identity building and online safety was (and continues to be) sorely lacking so those of us who grew up in the age of the internet have had to figure things out as we determined the ways in which apps and platforms would work for us and navigating the interface and content changes forced on us by the platform owners (think about Instagram’s proposed removal of the Likes count display and Tumblr’s banning of sexual content as two recent examples).

Unfortunately, since more and more people rely on social media for communication, education and entertainment, these conversations need to occur in places where more people are likely to see and engage in them. So, complex messages have to be distilled down to fit with platform formats. And, because we’re human and we like repetitive formats, we tend to consume information in the ‘easiest’, most condensed option available. Oftentimes, this results in us losing much of the nuance in conversations. It can also result in well-meaning conversations doing more harm tham good.

Taking the racism out of your internet use

Now, let’s consider your own online presence and how you might work antiracism into your internet use. First of all, look at who you’re following. How many educators, activists, researchers, artists, writers, musicians are Black, Indigenous and People of Colour? Now is the time to curate your feed in a way that promotes a diverse range of thinking, lived experience and action. Maybe you should unfollow people you know are refusing to learn and do the work to be antiracist. Maybe try and engage with people you know who are continuing to be racist and do the work so your pals from marginalised communities don’t have to.

One thing you should absolutely do is research the content you’re engaging with. Look into the arguments and the people sharing them – are they the OP (original poster), or are the reposting other people’s content without credit? Are these people experts, are they new to the conversation? Are there others you can learn more from and who share more nuanced takes on big issues? We’re all so quick to hit Share, but we don’t spend nearly enough time researching to ensure we’re promoting informed individuals who actively work to minimise harm and work in antiracist ways. A quick internet search of “[name] controversy” or “[name] harm” will give you an overview, but search Twitter and Instagram too. Whisper networks often work by not tagging but still using harmful users’ names (or swapping letters for an asterisk to avoid pile-ons or other violence). And be ready to be wrong.

One of the biggest things you can do is be open to being corrected or challenged. We’re human. We won’t get it right all the time. Getting it wrong isn’t the end of the world – it’s an opportunity to learn and expand our understanding of an incredibly complex issue. Share your learning – if you weren’t aware, the likelihood is some of your social media followers won’t have known either. Openness and accountability are good practices to engage with in your internet use.

There’s not only one strategy for weaving antiracism into your online presence, but there are lots of steps you can take in decolonising your social media use that will help.

Digital Blackface and cultural appropriation online

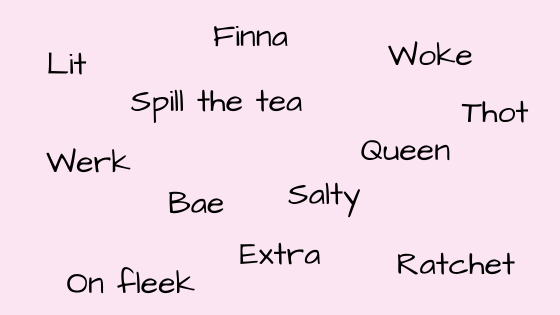

Think about where your internet use includes appropriation. Do you use African American Vernacular English outside of contexts where you are quoting somebody? What words do you search for in the Giphy library, and how many of those GIFs are stereotyped behaviours of Black people? Digital blackface is an issue I have been exploring for a few years. It’s real and it’s incredibly problematic. Teen Vogue published an article about Blackface in GIFs a few years back and I highly recommend you read it. Giphy hired a Cultural Editor, Jasmyn Lawson to address the imbalance of representation in GIFs. She was interviewed by i-D in 2018 on making GIFs more Black and the interview really stuck with me.

“I want to have GIFS that represent all types of black women: light-skinned, dark-skinned, heavy set, different sexual orientations, trans. And really make sure all the different sects of a certain minority group is being represented well in the media.”

Jasmyn Lawson, in an interview for i-D

That this was such a revolutionary step in 2018 really frustrated and upset me. But I was so inspired by Jasmyn’s work. It got me thinking about how I present myself online. Do I resort to racist caricatures? I certainly did. I take a lot more time in choosing GIFs and sharing memes now, considering what implicit messages they carry and whether they fall foul of racial stereotyping or appropriation.

There are multiple ways non-Black people have been appropriating Black culture, history, pain and joy. A recent example is the Breonna Taylor memes. The memeification of her murder, “Anyway arrest the cops who killed Breonna Taylor”, is a stark reminder that the ways we engage with content on the internet removes an element of humanity from the topics we’re discussing. An excellent article from Huffington Post explores the need for greater recognition by non-Black people of Black humour, joy, grief, pain and culture.

But the popularity of this one call for action has also highlighted the ways in which this current cultural moment is being commodified, trivialized and used as fodder for performative allyship.

Zeba Blay, Huffington Post

Removing racism from your social media use

We need to bring our internet interaction back to a place of intention and reflection. If we’re going to post online, we have to take away the mindless scroll and actively participate. That means stopping to think about why we’re consuming the content we are, what potential impact this could be having on others, and how we want to engage with other people. In many cases, our use won’t change. But you might consider not retweeting harmful tweets – retweeting tells the algorithm to amplify the post and will potentially put more people at risk of harm. You might add a contextual message to the Instagram post you share to your Story. Maybe instead of a Story, you record a video to give you more space to communicate effectively and save it to your highlights so you can reflect on it later and have it accessible beyond the 24 hour mark.

Social media, but make it antiracist

How you present yourself online is how people will likely remember you, especially during times where in-person meetings are limited and more of our communication is occuring through screens (with or without video and microphones enabled). Actively working antiracism into your internet use, particularly your social media, is a crucial step in decolonising your online presence. The internet doesn’t start or end with social media, but as it continues to play a huge part of our lives in how we curate our digital existence, portray our lives, consume content, learn, engage in activism and so much more, it’s certainly a great place to start building antiracism into your daily life.

This is a huge topic. Technically it’s a combination of multiple huge topics, which makes it even bigger. Such a mammoth needs more than one 2,000 blog post/essay/thought piece/brain dump to investigate it. I have lots of thoughts and feelings about lots of things that are happening online. I’ll publish new blog posts when I have the energy and the words to verbalise the abstract ideas that are bouncing around my brain. As you can probably tell from this ridiculously long blog post, I’m incredibly passionate about these topics. Not least from a research perspective, but as a human who works, researches, learns, connects and emotes a lot online it’s important to me that I reflect regularly on what I’m seeing and doing. I hope this post has given you some food for thought too.