We hear the word a lot – misinformation. We hear about its pervasiveness on social media even more. But what does misinformation mean? What are the implications of misinformation on social media platforms? Why does misinformation pose such a threat elsewhere?

I think I should start by saying that I HATE the euphemistic term misinformation. It’s misleading. It suggests it’s misinformed. That’s what the prefix mis- tends to preclude in English words. Some lack of intention or lesser harm. Far less insidious than, say, lies or deceit. But that’s exactly what misinformation is. It’s false data or information. I do wonder why those who coin the terms for these things might have settled for misinformation. As much as I hate to admit it, I find Fake News to be a more appropriate term – it at least highlights a problematic nature with the news that has been falsified; fake connoting some undesirable quality (think of how fake is used to deride or negatively frame, for example, people, tanning products, vegan meat substitutes). Like most things, I’m finding the need to use literal language to avoid minimising or trivialising the issue. As fun and creative as figurative language is, it often results in dampening the urgency or gravity of a situation. We need to call these instances of false information what they are, not only to highlight them as a problem but to consider why they are occurring with what appears to be exponential frequency and danger. In other words, where is this happening with the intention of lying and consequently causing harm?

On social media, misinformation largely refers to articles shared by users which are not factually accurate. An issue with social media information sharing is the platform’s inability to fact-check. You usually have to leave the platform to check out the facts. For several reasons, we have grown to take our social media information at face value, not going off-platform to research the claims of clickbaity headlines, Tumblr conversations or curiously images with blocks of text lacking any references. Despite the dubious nature of these items, we still feel compelled to believe them – because why would anyone lie?

We know, however, that this flaw in our social media use is absolutely used against us. Carole Cadwalladr presented evidence of the Brexit campaign’s misinformation use in Facebook ads which undoubtedly influenced many people’s decisions in the vote. American congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez was recently applauded for her targeted questioning of Mark Zuckerberg in Facebook’s lack of fact-checking capabilities on political ads, despite evidence of political ads publishing blatant lies and doctored statistics to influence voting in the last election.

Facebook has recently implemented fact checking on some posts where the information is queried so users can be reassured or dissuaded from sharing posts. But Facebook is one platform – the issue goes much further.

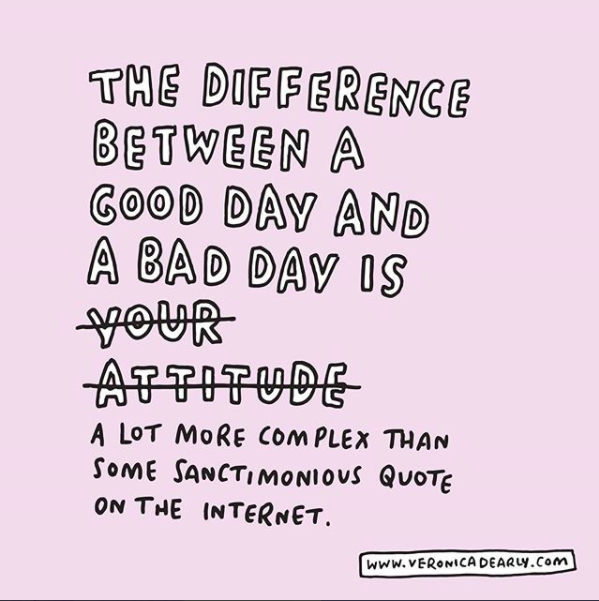

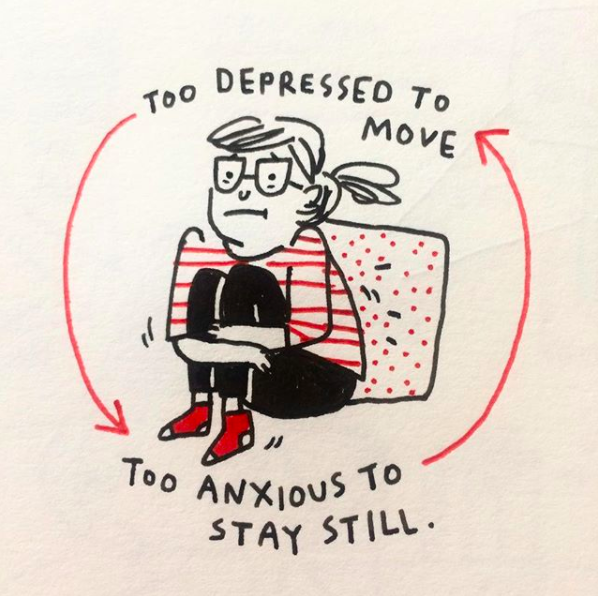

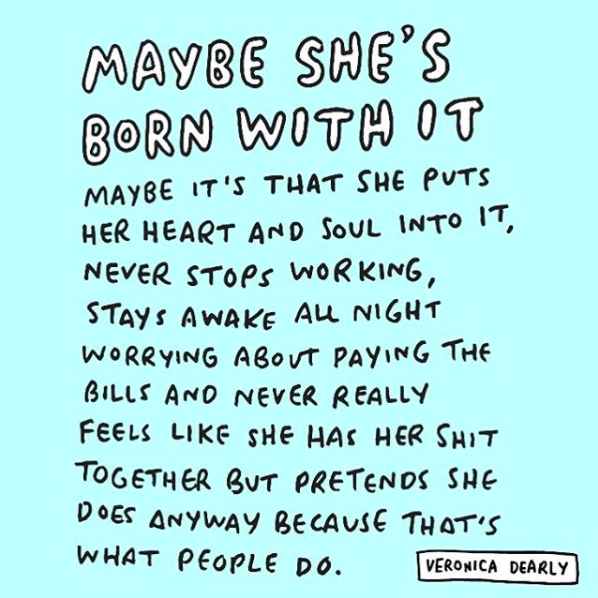

Instagram in particular has become a hub for educational resources (I recently wrote about some of the issues I have with knowledge sharing on social media). Anyone can access Canva and create aesthetically pleasing images with text in funky fonts, make reasonably argued claims and publish them for the world to share and repost without any investigation. Without a large enough audience, it’s impossible to include Swipe Up links in Instagram Stories to direct people to further reading or resources. We all get a website URL we can use, but how many people actually click through? Part of the problem is the functionality of Instagram forces users to exit the app if they want to find more information on a topic – user psychology predicts that people would rather stay in-app and keep scrolling. That’s why Instagram created a web browser experience for Swipe Up links that doesn’t require you to jump to another app like Chrome; it happens within Instagram itself. We’ve been conditioned by these apps’ design to expect information to be brought to us, not for us to go out seeking it. And who would prefer to switch apps (a clunky user experience at the best of times) when they could take the easy route and keep scrolling to find other aesthetically pleasing grid pic with big statements in bold font.

Of course, there’s also the issue of referencing and sources for these educational content squares. While many educators and content creators do reference and acknowledge where information comes from, transparency is difficult to maintain on platforms like Instagram. Largely because they weren’t built for this use – although Insta HQ devs could definitely tackle this problem if the company’s owners (Facebook) cared enough.

WhatsApp is another platform – whether you consider it inherently *social media* or not – that we need to think about. Communities globally use WhatsApp in different ways, but group chats are a common feature across the world. And in these group chats, you often see viral content shared and repurposed. But WhatsApp has no feature for fact-checking or flagging misinformation before the content is forwarded to another chat. And with its perceived distance from the internet/Google Chrome, are we even less likely to leave the app and check out the claims of a meme or supposedly screenshotted image of advice from an unnamed doctor who advises drinking lots of water will dissolve COVID-19 and save our immune systems?

So what can we do to combat misinformation on social media?

Firstly, we can be more conscious of the information we’re consuming and think more critically about what it’s telling us. This isn’t really anything new – people have been sceptical of The Media (namely newspapers, more recently the BBC) and the biases or skewed perceptions they have portrayed of certain issues, especially as they relate to governments and powerful companies or individuals. We can definitely apply this scepticism (while avoiding falling down a full on conspiracy rabbit hole) to social media content, particularly paid ads or sponsored content. However that puts the onus on us as users, which, in my opinion, errs on the side of victim blaming; “It’s your responsibility to stay vigilant of your surroundings and whose content you consume” has echoes of “Don’t walk home by yourself to avoid being attacked” and other harmful rhetorics laid at the feet of victims of rape culture.

Instead, you can push content creators to include more transparency in sharing their sources. Gently remind your friends who keep sharing posts without any evidence to back up claims that they should be fact-checking before hitting the Share button. For ads or content that looks suspicious, report it to the platform; put the onus on them to improve their safety mechanisms. There are regularly petitions circulating to push the Government to regulate social media platforms (especially around political advertising) – sign those petitions.

I realise that these are still actions you have to take, but they don’t focus on policing your own actions or force you to keep yourself safe, instead they bring others into the conversation to tackle this issue from a number of angles. This multi-angle approach is crucial if we’re going to see any real change for the better when it comes to tackling the deluge of false information spreading through social media.

Being aware and having your eyes wide open is really important here. It’s exhausting; it’s tedious; it’s infuriating when you realise just how flawed so many of these systems are. Those aren’t reasons to remain complacent. The information is there. The proof of lies being spread via social media is abundant. We have a duty as digital citizens and as app users to take ownership of our own media consumption, and by extension, our exposure to education and information gathering.

EDITED ON 13TH AUGUST TO ADD

The BBC published a news article on 12th August 2020:‘Hundreds dead’ because of Covid-19 misinformation.

At least 800 people died around the world because of coronavirus-related mininformation in the first three months of this year…about 5,800 people were admitted to hospital as a result of false information on social media. Many died from drinking methanol or alcohol-based cleaning products. They wrongly believed the products to be a cure for the virus.

Alistair Coleman, BBC News

So misinformation is not just dangerous politically, but potentially lethal. The findings of this research is surely enough to highlight the very real threat of embodied harm that misinformation poses, even if the purposefully false political advertising doesn’t strike you as wholly problematic.